The core idea is to move beyond designing just for function and to instead foster collaboration between all stakeholders (e.g., design, manufacturing, supply chain) from the very beginning.

Traditional Product Development vs. Design for X

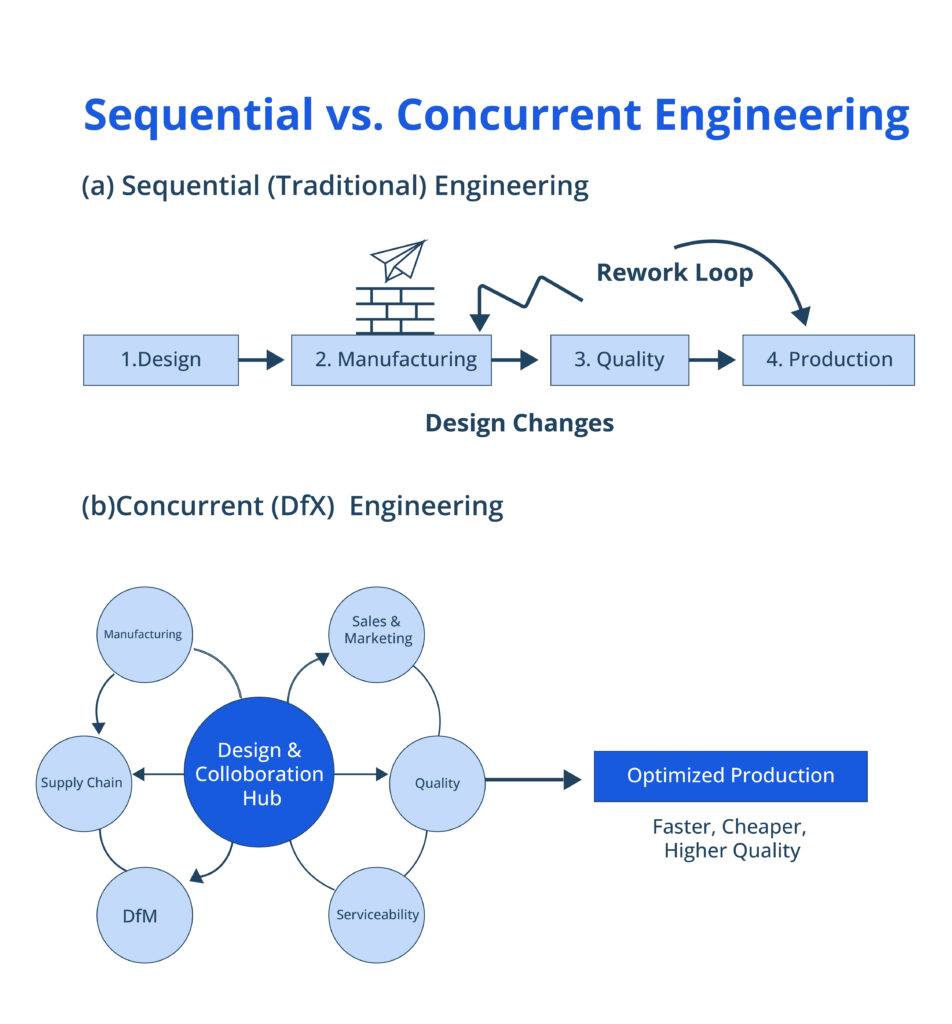

The traditional product development model is often called sequential engineering.

- Design teams work in relative isolation to create a product optimised for function and performance.

- The “finished” design is then “thrown over the wall” to the next team (e.g., manufacturing).

- Manufacturing then discovers the design is difficult or costly to produce. Procurement finds that components are expensive or hard to source. Quality identifies testing challenges.

- Each discovery forces a costly iterative loop, sending the design back for changes, which extends timelines and increases costs.

The Design for X approach uses a concurrent engineering model to reverse this. It brings “downstream knowledge” (from manufacturing, procurement, quality) “upstream” into the early design phase.

This concurrent method identifies and resolves conflicts early, when changes are fastest and cheapest to make. It shifts the timeline to allow for a longer, more collaborative “incubation period” in the design phase to prevent major setbacks at later stages.

DfX Core Principles

While DfX includes many specific methodologies, they are all guided by a set of core principles. These principles guide the design decisions and collaborative approach for any “X” you are trying to optimise.

The table below provides a quick summary of these principles.

| Principle | Definition & Critical Importance |

| Cross-Functional Collaboration | Involving all stakeholders (manufacturing, procurement, quality) from the start. This prevents costly errors by incorporating real-world constraints early. |

| Early Integration | Applying DfX principles during the conceptual phase. Making changes at the design stage is exponentially cheaper and faster than after prototyping or in production. |

| Simplification | Reducing part count and complexity. Simple designs are cheaper to make, easier to assemble, and more reliable. |

| Standardisation | Prioritising standard, off-the-shelf components and materials. This reduces costs, shortens lead times, and improves reliability with proven parts. |

| Mistake-Proofing (Poka-Yoke) | Designing features that physically prevent incorrect assembly (e.g., asymmetric holes). This eliminates errors and improves quality. |

| Measurable Objectives | Using quantitative metrics (like cost estimates or defect rates) to make objective, data-driven design decisions instead of relying on subjective opinions. |

| Iterative Refinement | Treating DfX as an ongoing process, not a one-time checklist. This allows for continuous improvement as the design matures. |

Cross-Functional Collaboration

This is the most important enabler. Design engineers must collaborate with all other stakeholders (manufacturing, procurement, quality, etc.) from the very start of the project even if they have a wide circle of competence. A specialist in manufacturing or supply chain can identify real-world constraints, costs, and supplier risks that a design engineer might miss while working in isolation.

Early Integration

DfX principles must be applied during the conceptual and preliminary design phases, not after the design is “finished”. Flexibility is highest and the cost of change is minimal at the beginning of a project. Finding a flaw after prototyping or in production is exponentially more expensive and time-consuming, as it requires redoing detailed design work.

Simplification

A simple design is often the best design. Simple designs are typically cheaper to manufacture, easier to assemble, fail less frequently, and are more accessible for maintenance.

Achieving this simplicity often requires significant collaborative effort from the entire team.

Standardisation

This principle prioritises the use of standard, off-the-shelf components, materials, and solutions instead of custom-designing everything. Standard components reduce costs, shorten lead times, and improve reliability because they are readily available and have been time-tested.

Mistake-Proofing

If it’s possible to make an error, someone will make it. Principles like mistake-proofing, fool-proofing, or poka-yoke are designed to avoid errors through physical constraints, distinctive orientation features (consider the effort involved in correctly plugging in a USB stick), and assembly sequences/features that ensure correct execution.

Simple features like asymmetric holes, notches, or unique connectors can eliminate assembly errors and improve quality. A great welding assembly needs no more than the general dimensions and item numbering in the technical drawing.

Measurable Objectives

DfX methodologies use quantitative metrics to evaluate design choices, rather than relying on subjective opinions. Metrics like estimated assembly time, manufacturing cost estimations, and reliability calculations allow for objective, data-driven decisions when comparing different design alternatives.

Iterative Refinement

DfX is not a one-time checklist but an ongoing process of improvement throughout the development cycle. The goal is to identify challenges and opportunities for optimisation as early as possible. As a design matures, new information will emerge, and DfX principles guide the continuous refinement of the product.

These principles manifest as specific practices: design reviews with cross-functional teams, checklists for each DfX domain, analysis tools for cost and complexity and design guidelines that capture institutional knowledge.

How DfX Relates to Other Design Methodologies

Design for X isn’t a standalone system that competes with other process improvement philosophies. Instead, DfX is a set of tools and practices that complements and strengthens methodologies like Lean, Six Sigma, and TQM.

Concurrent Engineering

Concurrent engineering (using cross-functional teams and parallel workflows) is the enabler of DfX. DfX provides the specific rules and guidelines (like DfM, DfA) that concurrent teams use to make decisions. You cannot effectively implement DfX if your company structure is still siloed.

Lean Manufacturing

Lean focuses on eliminating waste (e.g., overproduction, defects, unnecessary inventory) to improve efficiency and reduce costs. DfX principles like simplification (fewer parts), standardisation (standard components), and DfM (Design for Manufacturing) are all powerful tools that directly support Lean’s goal of eliminating waste at the design stage.

Six Sigma

Six Sigma is a data-driven methodology focused on reducing process variation and defects to achieve extremely high production quality. DfX supports this by addressing variation at the design level. For example, a design that allows for wider tolerances while still functioning perfectly is inherently robust and less sensitive to normal process variations, making Six Sigma goals easier to achieve.

Total Quality Management (TQM)

TQM is a management system that makes quality the responsibility of every stakeholder in the company. DfX mirrors this philosophy perfectly by including all stakeholders (manufacturing, quality, etc.) in the design process to identify and prevent potential quality issues before they are ever created

Ultimately, DfX should be viewed as a complementary approach; it offers tools that enhance and integrate with other existing methodologies, rather than serving as a competitive framework.

DfX Methods

DfX methodologies can be categorised by the main product lifecycle stages they address: development, production, use, and disposal. This section explores these phases, their goals, and the specific methods used to achieve them.

Development Phase

The development phase focuses on accelerating the timeline in the early stages. Key goals include shortening time to market, ensuring testability, and guaranteeing regulatory compliance from day one.

The primary Design for X methods in this phase are:

| Methodology | Focus Area |

| Design for Short Time to Market (DfTT) | Speed, modularity, and design reuse. |

| Design for Testability (DfT) | Validation, diagnostics, and easy inspection. |

| Design for Compliance (DfC) | Regulatory adherence, safety standards, and certification. |

Design for Short Time to Market (DfTT)

The more custom a design is, the longer the project will take. Design for Short Time to Market emphasises reusing existing designs, creating modular components that fit different needs with minimal customisation, and using standard components whenever possible.

- Simplification: Reduces decision-making and iteration cycles.

- Validation: Simulation acts as the first step before physical builds, while rapid prototyping allows for quick product testing.

The main trade-off is a potential limit on innovation, as relying on existing solutions discards the possibility of improving them. However, the speed advantage is often decisive.

Example: Volkswagen’s MQB approach significantly reduces development time for each new model by reusing validated suspension, powertrain, and safety structures across different vehicles.

Design for Testability (DfT)

Design for Testability ensures products can be effectively tested and validated. Key principles include ensuring access for testing equipment (considering existing assets), incorporating self-testing capabilities, and enabling isolated subsystem testing before full integration.

- In Electronics: This means including accessible test pads and diagnostic ports.

- In Mechanical Engineering: It involves providing proper access for inspection tools and clear reference surfaces for measurement. Clear criteria must be established for passing or failing tests to ensure objective evaluation.

The benefits are fast, easy testing, simplified troubleshooting, and reduced warranty costs. The trade-off is slightly higher design complexity to include these extra features, but the cost savings from accurate testing typically outweigh this investment.

Example: Modern smartphone manufacturers incorporate test pads on circuit boards to allow functional testing of key subsystems (e.g., power delivery, sensors) before final assembly.

Design for Compliance (DfC)

All industrial products must adhere to regulatory, safety, and industry standards. Design for Compliance prioritises these requirements from the very start to avoid costly retrofits.

Engineers must identify relevant standards early—such as emergency stops for machinery—and design to meet them. Industry-specific considerations include:

- Electrical: Safety standards and electromagnetic compatibility requirements. (EMC).

- Medical: Strict device regulations and material restrictions.

- Pressure Vessels: Specific design codes and safety factors.

This list grows with every new market entered. Failing to follow DfC can delay commercial launch and increase legal risk. While “doing things right” upfront costs more, it ensures a smooth market entry and protects revenue.

Example: Collaborative robot manufacturers must design for ISO 10218 and ISO/TS 15066 compliance, integrating force-limiting actuators, rounded edges, and emergency stop systems directly into the hardware.

Production Phase

The production phase zooms into the specific stages of manufacturing, from initial planning to final inspection. This phase utilises the widest range of DfX methods to optimise cost, assembly speed, quality, and supply chain resilience.

The primary Design for X methods in this phase are:

| Methodology | Focus Area |

| Design to Cost (DfC) | Meeting cost targets without sacrificing quality. |

| Design for Assembly (DfA) | Simplifying assembly to reduce errors and labor time. |

| Design for Manufacturing (DfM) | Optimising designs for specific production processes. |

| Design for Inspection (DfI) | Ensuring critical features can be easily verified. |

| Design for Supply Chain (DfSC) | Reducing supplier dependency and procurement risks. |

Design to Cost (DfC)

Design to Cost (or Design for Cost) optimises product design to meet specific cost targets while maintaining required functionality and quality. This is a strategic approach that treats cost as a rigid design requirement from project inception, not an afterthought.

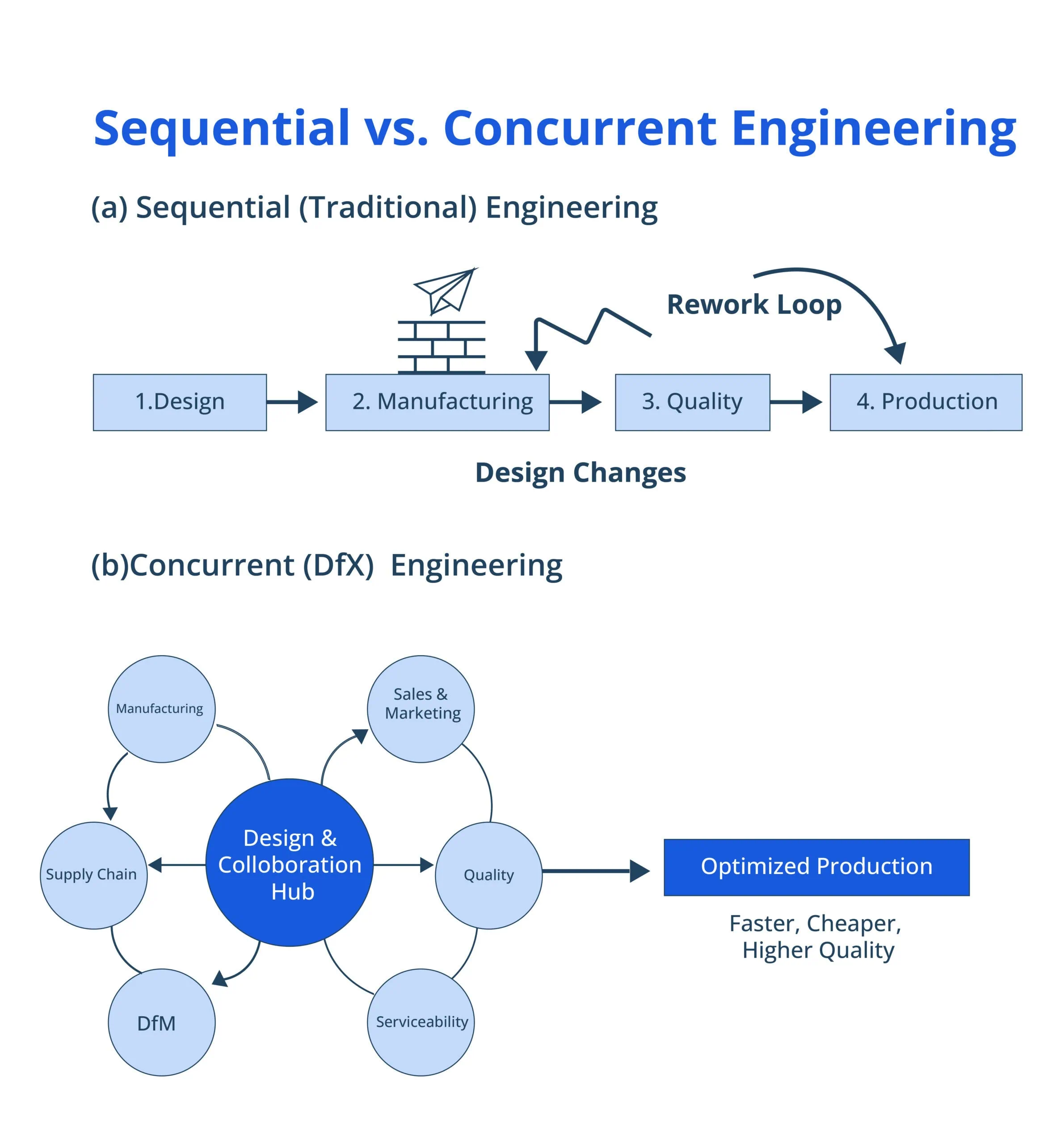

It involves minimising part count, selecting standard components, and choosing appropriate processes for the production volume. Engineers can utilise instant quoting software to quickly compare the costs of different designs and quantities, which assists the process. Furthermore, manufacturing and procurement specialists can contribute valuable insights regarding the various available options.

When using the Design to Cost approach, it’s essential to remember that it’s a strategic approach that treats cost as a design requirements from the project inception. But it’s not about lowering the production cost by any means.

Example: IKEA’s furniture design incorporates DfC principles at every stage. By using standardised parts and low-cost, high-strength materials like honeycomb cardboard cores sandwiched between fiberboards, they lower costs significantly while maintaining appearance and functionality.

Design for Assembly (DfA)

Labor at the assembly stage often represents a significant portion of overall manufacturing costs and is a major source of quality issues. Design for Assembly aims to simplify this process to reduce errors and speed up production .

The main tools for achieving these goals are:

- Minimising part count to reduce complexity.

- Designing for top-down assembly to utilise gravity.

- Creating self-locating features and using symmetry to prevent orientation errors.

- Mistake-proofing

- Smart fastening like snap-fits or pre-threaded holes.

- Modular subassemblies to enable parallel work

- Accessibility

The clear benefits are reduced assembly time, fewer errors (even with less operator training), and improved product quality.

Example: Dyson’s dust bins are transparent and use snap-fits. This makes the assembly process easy to follow and mistake-proof, ideal for both prototyping and mass production.

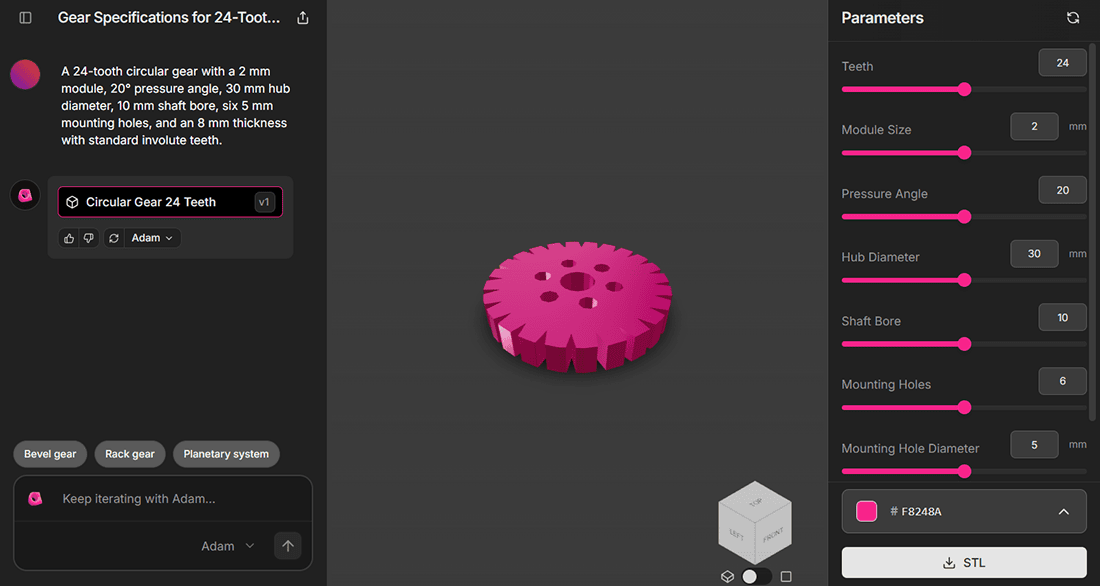

Design for Manufacturing (DfM)

Design for Manufacturability tailors the design to the reality of the manufacturing floor. Considering the availability and limitations of production methods ensures reasonable costs, short lead times, and strongly diminishes the danger of reclamations with high quality.

Key principles include preferring widely available processes, designing for standard tooling, and selecting materials that are easy to machine or form. A design that many manufacturers can produce without extensive back-and-forth communication ensures supply chain stability.

It’s great to have a production engineer available for consultation if questions arise, as there are plenty of specifics to consider. A lot of the best practices also depend on the production volumes.

Examples: Recommended bending radii for material thickness in press braking, proper placement of parting lines in die casting and using justifiable tolerances in CNC.

Design for Inspection (DfI)

Design for Inspection ensures critical features can be effectively measured and verified during production and throughout the product’s operational life.

Inspection should be easy and ideally require no specialised equipment.

Essential strategies include:

- Providing easy access to critical dimensions.

- Incorporating clear datum features for consistent measurement.

- Avoiding indirect measurements that require calculation.

A great design considers both production floor measuring setups like CMM machines as well as field inspection equipment like calipers, micrometers and simple visual checking.

Well-designed inspection features enable statistical process control (SPC) and early detection of mistakes before a full batch of faulty parts is produced.

Example: Aircraft wing spars feature inspection ports that provide access to internal bolt connections and structural joints, allowing for critical safety inspections without requiring wing disassembly.

Design for Supply Chain (DfSC)

The supply chain encompasses everything from raw materials to manufacturing partners. Design for Supply Chain aims to reduce dependency on single sources and mitigate procurement risks.

Design engineers play a crucial role by selecting materials and components that are readily available from multiple sources

Even if identical purchase parts have many sellers, they might come from a single source. Sometimes there are many companies that make products following the same main measurements, or many suppliers for spare parts (e.g. B parts in automotive).

Material selection is crucial, but sourcing uncommon (“exotic”) grades can be challenging, a fragility recently exposed by global supply chain issues. Yet, these materials are often vital and sometimes the only feasible choice.

Reusing similar purchased parts across designs gives procurement teams negotiation leverage due to cumulative quantities.

Overall, considering supply chains clearly offers reduced costs, shorter lead times, lower inventory, and resilience during turbulent times.

Example: A standard approach is to limit the variety of standard fasteners employed, generally to between 20 and 40 unique types. This typically encompasses common metric dimensions (e.g., M6, M8, and M10), each offering a selection of two to three length variations.

Use Phase

The use phase looks forward into the product’s operational life, focusing on performance, safety, and longevity. The goal is to ensure the product works as intended, protects its users, and can be easily maintained.

The primary Design for X methods in this phase are:

| Methodology | Focus Area |

| Design for Safety (DfS) | Identifying and mitigating hazards for users and operators. |

| Design for Quality (DfQ) | Building quality into the design through robust specifications. |

| Design for Reliability (DfR) | Maximising lifespan and minimising failure rates. |

| Design for Maintenance (DfM) | Simplifying servicing and component replacement to reduce downtime. |

Design for Safety (DfS)

Safety is paramount. Design for Safety identifies and mitigates hazards to protect users, operators, and service personnel throughout the product lifecycle. While standards exist, engineers must also apply common sense to their designs.

Key considerations include:

- Eliminating Hazards: Eliminating sharp edges and corners, covering up moving parts, using guards, labeling important elements, intuitive control mechanisms and fool-proofing all play an important role.

- Engineering Controls: Covering moving parts, using guards, and implementing fail-safe mechanisms.

- Warnings: Providing clear labels and indicators if something is not working properly.

- Ergonomics: Considering the long-term exposure of machine operators to chemicals, electrical risks, or repetitive strain.

Example: SawStop table saws incorporate a revolutionary safety mechanism that detects contact with skin and stops the blade within milliseconds, preventing serious injury.

Design for Quality (DfQ)

Quality essentially means “Does the product work as intended right out of the box?”. Design for Quality focuses on consistency.

Key approaches include:

- Robustness: Designing robust mechanisms to work under all variations of normal conditions.

- Tolerancing: Selecting appropriate tolerances that balance function with manufacturing capability.

- Failure Prevention: Using proven materials and processes, and running simulations (like FMEA) to discover potential risks early.

Good quality builds brand trust and customer satisfaction while significantly reducing warranty payouts.

Example: Apple’s MacBook unibody design machines the entire chassis from a single block of aluminum using CNC milling. This replaces the traditional method of welding multiple stamped pieces together, eliminating alignment issues and weak points.

Design for Reliability

Reliability is about how long your product maintains high quality without unexpected breakdowns. A single part failure can halt production in an entire factory, so critical parts must be identified early.

- Safety Margins: Applying adequate safety factors for maximum loads.

- Environmental Protection: Selecting materials that can withstand the specific operating environment (heat, moisture, chemicals).

- Design Philosophy: Engineers can design for longevity under strict maintenance guidelines or design to withstand misuse. Ideally, DfR accounts for both.

Example: Many car manufacturers use timing chains instead of timing belts. While chains add cost, they last significantly longer and reduce the risk of catastrophic engine failure, improving overall vehicle reliability.

Design for Maintenance

Even reliable products have parts that wear out. Design for Maintenance focuses on making it as easy as possible to get things back up and running.

Modular design that enables component replacement without complete disassembly is important. So is using parts that can be easily found on the market. Access to wear items has to be considered. Also, self-diagnostic features and visible wear indicators simplify monitoring and troubleshooting.

While often overlooked, thorough documentation, such as service manuals, proves immensely valuable when maintenance is eventually required. Similarly, for projects utilising 3D printing, knowing the most durable materials for 3D printing is a crucial consideration.

Machine uptime is critical in a factory setting. Good DfM ensures that when a mechanism wears, work can resume quickly.

Example: Modern server racks use hot-swappable power supplies, fans, and drive bays with tool-free front access, allowing technicians to replace faulty components in 2-3 minutes without any shutdowns.

Disposal Phase

The final phase of the product lifecycle addresses what happens to the product once it reaches the end of its useful life. This phase is increasingly critical due to regulatory pressure and consumer demand for environmentally responsible products.

The primary Design for X methods in this phase are:

- Design for Sustainability: Minimising environmental impact through material choice and waste reduction.

- Design for Product Lifecycle: Enabling reuse, refurbishment, and effective recycling.

Design for Sustainability

Sustainability has become a central pillar of modern engineering design, addressing regulatory requirements, customer expectations, and corporate responsibility.

The first step is material selection. Ideally, materials should be recyclable or biodegradable. Material usage efficiency is also key, especially for high-volume production where even a minor reduction in material mass significantly lowers the environmental footprint. Sourcing materials locally can further reduce the carbon footprint associated with transportation.

Engineers must also design for material separation. Combining inseparable materials (like overmolding certain plastics onto metal) can render a product unrecyclable. Another critical aspect is power efficiency; lowering the energy required for a product to perform its task makes it inherently more sustainable.

Example: Cities replacing traditional incandescent traffic signal bulbs with LED equivalents reduce energy consumption.

Design for Product Lifecycle

Design for Product Lifecycle extends value beyond the initial use phase through reuse, refurbishment, remanufacturing, and recycling strategies. This “circular economy” approach treats end-of-life as an opportunity rather than a waste disposal problem .

Key pillars of this methodology include:

- Designing modular systems that allow for component replacement and upgrades,

- Ensuring durable construction to support multiple use cycles,

- Clearly marking materials to facilitate sorting at recycling facilities,

- Standardisation also plays a role, allowing components to be repurposed across different product generations.

Example: Fairphone designs smartphones with modularity at the core. Users can easily replace batteries, camera modules, and displays on their own, significantly extending the device’s lifespan and reducing e-waste.

Design for Excellence is “Just Good Design”

In many ways, the principles of Design for Excellence might simply sound like “good design.” However, DfX formalises these concepts into a systematic methodology that emphasises collaboration and a company-wide commitment to every facet of the product lifecycle .

Designs that leverage these principles are not just functional; they are thoughtful, long-lasting, fit for purpose, and sustainable. While implementing DfX requires more effort and resources upfront, the return on investment—through lower costs, higher quality, and happier customers more than repays the work .

Europe

Europe  Türkiye

Türkiye  United Kingdom

United Kingdom  Global

Global

Login with my Xometry account

Login with my Xometry account  0

0

Comment(0)