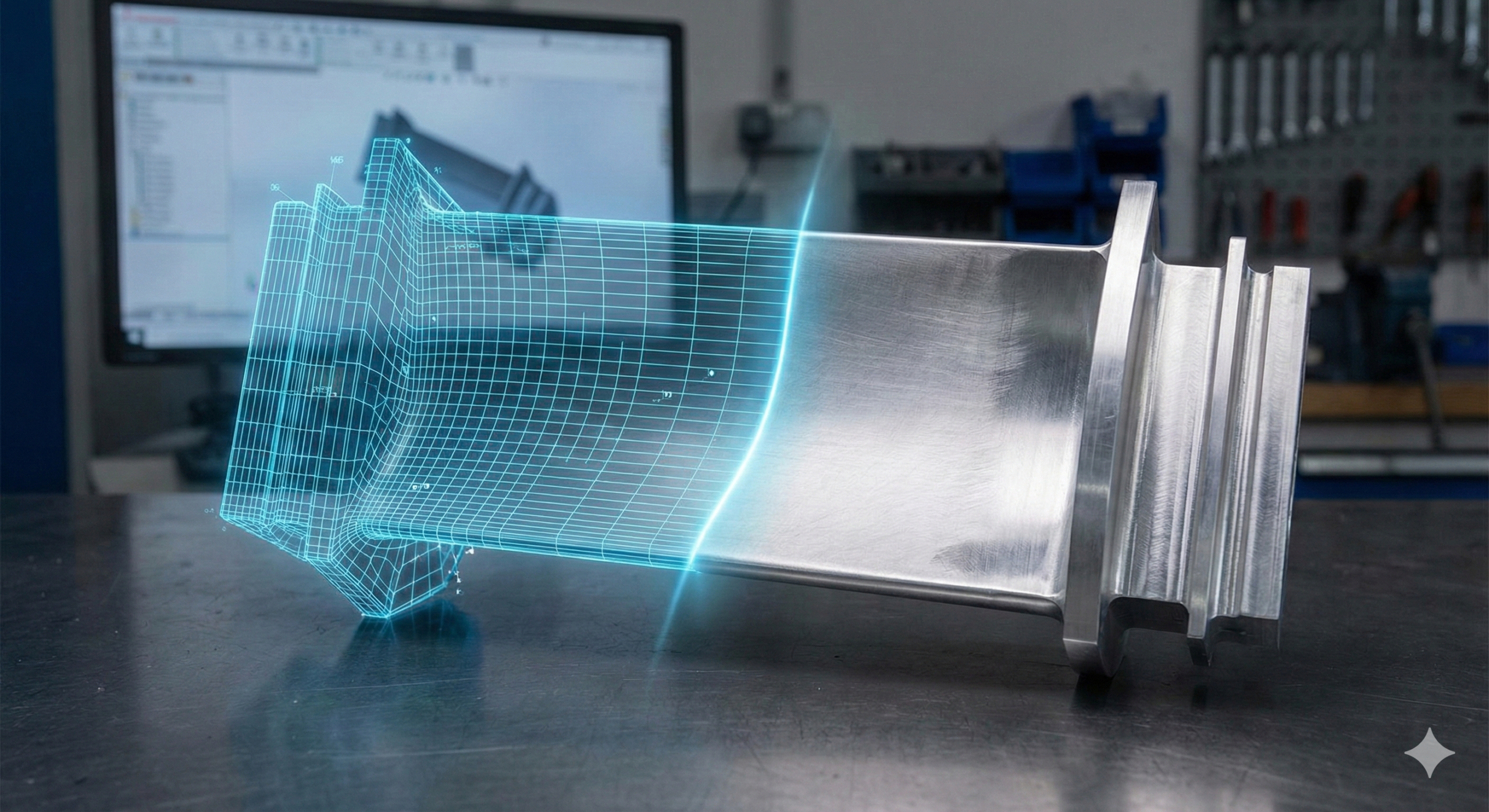

By adopting DfMS, engineers can design a product with efficient maintenance and service in mind starting from the initial design process, rather than facing unpleasant consequences later.

Design for Maintenance and Design for Serviceability are combined into the single term (DfMS) because they share the same essential goal: to reduce equipment downtime. However, they differ in content and focus. To distinguish the line between Maintenance and Service, it is necessary to examine the nature of the activities carried out to reduce downtime.

Design for Maintenance vs Design for Serviceability

Design for Maintenance deals only with the fundamental design characteristics of a device, assembly, or machine. It targets the ease of performing maintenance tasks on devices in practical, real-life operating conditions. Whether maintenance requires dismantling the device to its basic components or, conversely, all replaceable parts can be accessed and replaced easily and effortlessly, depends entirely on these design choices.

In some cases, well-planned design enables equipment maintenance to be carried out without stopping the device or interrupting its normal operation. It is fundamentally about the inherent design of the device, and nothing else.

Design for Serviceability (DfS) is less commonly applied, yet service plays a crucial and often underestimated role in minimizing downtime. DfS also addresses the fundamental design characteristics of a device, but in a broader and more integrated context, often involving elements that lie outside the device or machine itself and interact with the surrounding environment.

DfS is truly effective only when the device provides automatic status information through reliable self-diagnostics and is simultaneously supported by a well-designed, appropriate service infrastructure.

A well-designed and organized support system ensures that the appropriate maintenance specialist receives information about maintenance needs promptly and reaches the required location quickly, equipped with the right accessories and necessary tools. Furthermore, instructional materials for performing maintenance must be clear, simple, and easily accessible. This aspect of DfMS is more commonly found in modern smart devices outfitted with onboard communication electronics and software programs.

Ensuring Maintainability

Maintenance is technical work that sustains the health of the asset. While each product group has its own specific maintenance tasks, general activities can be identified:

- Visual inspection and testing

- Cleaning and lubrication

- Removing waste

- Tightening, adjusting, and calibration

- Replacement of consumables

- Software updates

These tasks typically require a trained technician to execute them, following maintenance rules documented in the device’s service manual. Even a well-designed device or mechanism requires periodic maintenance according to a set schedule to ensure high operational uptime.

Ensuring Serviceability

Service is a broader process or activity; it may include maintenance but also encompasses customer interaction through modern technologies, logistics, and documentation. While some tasks can be performed by a customer’s representative during normal operations, others require a maintenance engineer.

The following overview illustrates how maintenance actions are connected within a broader Service system context:

- Remote Support: Visual inspection, testing, cleaning, lubrication, tightening, adjustment, and calibration supported by teleservices or Assisted Remote Repair/Maintenance.

- Predictive Systems: Waste removal and consumable replacement supported by predictive maintenance and remote condition monitoring (E-maintenance).

- Software: Software updates performed remotely with the customer’s permission.

- Infrastructure: The availability of service engineers, consumables, and customer-operated small warehouses ensured by organized service providers.

- Support & Lifecycle: 24/7 web-based helpdesk support, warranty aspects, and end-of-lifecycle utilization programs.

All of these elements should be organized by the producer with the help of product development team members. Planning and anticipating everything that happens with the product during its lifecycle during the development phase is the essence of service/maintenance-centric design

Example Cases: DfM vs. DfMS

To illustrate how maintenance and service support each other, let’s examine an example using a modern multifunctional printer.

The DfM Approach (Design for Maintenance Only)

Our test object is a printer well-designed from a pure Design for Maintenance (DfM) perspective. Customer “X” calls for service due to a paper pick-up problem, reporting only that the printer is unable to print just 30 minutes before an important general meeting. Slight problems had started a week earlier but were ignored until the situation became urgent.

From the customer’s perspective, downtime began 20 minutes ago with the first unsuccessful print attempt. Even if the service company dispatches a specialist immediately, the maintenance action—replacing the paper pick-up roller and separation pad—can only begin once the specialist arrives. Thanks to DfM, the actual replacement work takes only five minutes due to a fast consumable parts exchange method. However, the total downtime has already exceeded a critical value, and the meeting is postponed.

The DfMS Approach (Design for Maintenance & Serviceability)

Same example: the device is well designed from DfMS point of view (actually, it is the same model, but in this case, it has supportive connection with an e-maintenance system designed by the producer or service provider).

Before the customer’s troubles start, the automatic part lifespan counter triggers an alert at the service provider’s side – requesting replacement of the pick-up parts at customer “X” due to wear.

If the customer is unwilling to pay for preventive maintenance and declines the service part replacement, the situation is still better, as the service company ensures that its warehouse includes the needed spare parts. Later, usually soon after the rollers reach the end of their lifespan, real problems may occur at the customer’s side, and in an e-maintenance environment, these will be detected and flagged again.

Normally, the service provider will ask the customer once more whether they would want to get the roller replaced. If the customer still refuses to order maintenance, there is still a greater chance to satisfy their needs by offering teleservice before an important meeting and during printer failure.

Firstly, the service provider knows exactly the situation with the customer’s printer. Secondly, most large printers use modular design and multiple paper feeding units for different paper types and sizes. In emergency cases, it is possible to readjust a less-used feeding tray for the required paper size, allowing continued use of the machine. Usually, customers are able to do this on their own; somebody just needs to tell them how.

And that is what Design for Serviceability enables.

It puts a lot more emphasis on the design process, especially in case of complex systems. But the higher initial investment should repay itself by allowing fewer mistakes and less operational downtime. The cost of maintenance is usually much lower compared to issues with reliability stemming from poor design choices.

Design Principles of DfMS

DfMS relies on several basic design principles and producer-specific additions. Common rules of Design for Maintenance and Serviceability include:

- Simplify design while ensuring maximum accessibility for replaceable parts, liquids, and consumables.

- Follow “Design for Safety during Maintenance” and ”fool-proof design” principles to prevent human error.

- Use modular design with standardized, durable consumables and similar parts.

- Integrate remote diagnostics, monitoring, and effective error-detection capabilities.

Broader service-side principles include:

- Design user interfaces with comprehensive remote options.

- Establish maintenance intervals that combine multiple activities.

- Train both users and service personnel.

- Ensure the availability of tools, consumables, spare parts, and service engineers.

Integrating Serviceability into the Design Lifecycle

Design for Maintenance and Serviceability is strongly connected with the wider Design for X (DfX) philosophy. Some of the Design for X family members that are directly or indirectly affected by DfMS are:

- Design for Assembly

- Design for Repairability

- Design for Obsolescence

- Design for Recycling

Well-designed, maintenance-friendly hardware is typically superior from assembly, repair, and disassembly perspectives. It reduces the time required to restore a device because consumable and spare parts are easy to access and replace. Furthermore, it takes less time to dismantle the device, facilitating the recycling of materials by even specialists with limited experience.

The DfMS process is an endless journey, as each new design iteration carries the risk of reducing maintainability. Therefore, development and design engineers must work in close contact with service engineers and carefully observe error data from e-maintenance databases of previous devices. This objective data is often more valuable than customer feedback, revealing the root issues behind problems and ensuring the ongoing reliability and maintainability of engineering systems.

Europe

Europe  Türkiye

Türkiye  United Kingdom

United Kingdom  Global

Global

Login with my Xometry account

Login with my Xometry account  0

0

Comment(0)